Home

Surviving Nuclear War in the 21st Century

How Likely is a Nuclear Attack in this Day and Age?

Given the existence of nuclear arms reduction and non-proliferation treaties between the major nuclear powers, the risk of nuclear war breaking out is lower than it was at the beginning of the Cold War. The risk has decreased so much that many people think that nuclear war, or the prospect of it, is something we left behind in the 1950s or 1960s.

However, the editors of the Bulletin of the Federation of Atomic Scientists have set their ‘doomsday clock’ to 100 seconds before midnight, signifying that the risk of nuclear war has actually increased. Indeed, international tensions have risen considerably in the last two years or so, bringing with them the possibility that a major war could break out between the world’s great powers. Naturally, a major conflict between these great powers could lead to all-out nuclear war.

Evidence of increasing international tensions can be found in China’s recent authorization for its coast guard ships and other naval vessels to open fire on any US naval vessels entering the Taiwan Strait, even if the US ships did not open fire first. In addition, several Chinese bombers and fighters recently entered Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) without permission, thus violating Taiwan’s territorial integrity in the process. Under international law, such a violation can be seen as an act of war.

Israel recently announced that it will be formulating a plan to deal with Iran, should it pursue any plans to develop nuclear weapons. The plan is being devised in the wake of Iran’s announcement that it is currently enriching its existing stocks of uranium to 20%, in violation of agreements made with the United States and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

While these announcements could be written off as just mere sabre-rattling, their tone is hostile and belligerent.

The bottom line? For as long as nuclear weapons continue to exist, there is a non-neglible risk that they will eventually be used. Consequently, it makes sense to prepare for the possibility of a nuclear attack occurring.

Is it Possible to Survive a Nuclear Attack?

The simple answer is yes, but with a few caveats. Survival depends on many variables, including where you are living when an attack happens. If you live in a major city that is a financial or industrial centre, has major airports or is a technology or communications hub, it’s likely a target.

Survival may also depend the kind of attack that is launched. For instance, in a counterforce attack, military bases and hardened government sites are targeted, while civilian areas are left alone. In a countervalue attack, civilian sites are targeted in an effort to demoralize the populace and decrease its ability to support the military through production of armaments and other supplies.

In a general nuclear war, both kinds of attacks are likely to happen. In addition, an attack may not happen all at once, and may come in the form of multiple salvos. Or an attack could come as part of a limited nuclear exchange. Most experts believe that a limited nuclear exchange is unlikely, as all warring parties may employ a ‘use-them-or-lose-them’ strategy, where they release all of their nuclear weapons at once rather than run the risk of losing some or all of them due to enemy counterattacks.

Early in the days of the Cold War, it was expected that cities or military bases would be hit with single weapons having a large explosive yield. These weapons would typically be delivered by manned bombers and might not necessarily totally destroy their targets, or even land where they were expected to land. The arrival of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) carrying multiple warheads meant that cities or other targets could be hit with clusters of smaller warheads arranged in such a way as to cause complete destruction and provide pinpoint accuracy. Major cities are most likely to be hit with such clusters, while smaller centres of strategic value will be targeted with single weapons. Accordingly, if you live in a major city, your chances of survival may be low unless you take shelter in a deep underground bunker, or reside in a far-flung suburban area.

Your best chances of survival are in towns or cities that are located far from major cities, military bases, or major industrial sites. Nonetheless, in the aftermath of a general nuclear attack, supplies of food, water and other essentials may be cut off or severely reduced, thus compromising your ability to survive.

In an all-out nuclear conflict, large numbers of medical facilities will also be destroyed. Getting medical treatment, if you have a serious medical condition that requires ongoing care, will be difficult, if not impossible. If your town or city was not directly attacked, all essentials, including medical care, may be available for only a limited time before running out, as re-supply sources will have been destroyed or damaged in the attack. Hordes of refugees who may descend upon your area in the days and weeks that follow an attack will also pose a threat, as will looters.

In some areas, even if they were not hit by nuclear weapons, radioactive fallout will be a problem. Cities or towns that are located far from target sites may have several hours or as much as a day or so to prepare for the arrival of fallout. Radioactive fallout also diminishes in intensity with time and distance. As a result, people living in distant locales may not need to shelter for long.

Will You Get any Warning of an Attack?

The simple answer to the question is, it depends on a variety of factors. If you live in a country that still has an operational civil defence system, chances are good you will be warned of an impending attack. In countries where no organized civil defence system exists, you may still receive a warning, although the warnings may be late, or reach only certain areas.

Certainly, if you live in one of the nuclear-armed countries like the United States or the United Kingdom, or any other developed, technologically advanced country, you will definitely receive warnings via radio, TV, text message or a pre-recorded message on your phone.

However, even in countries where communications networks are good, warnings may not get out in a timely manner. In the initial panic and confusion that will erupt after an attack is detected, efforts

will be made to determine if the attack is real, thus causing delay. Communications networks may fail or malfunction and cause further delay, or prevent warnings from being issued. In some areas, the first and only warning of an attack may be a very bright flash of light in the sky, followed by the chracteristic mushroom cloud of a nuclear explosion.

How much warning time you will get also depends on where you live. For instance, if you live on either the east or west coast of the United States, you may have as little as three minutes to prepare. This is because enemy submarines may be sitting a few thousand kilometres off either coast, and the missiles they launch will need only a few minutes of flight time to reach their targets.

If you live further inland, the missiles will take longer to arrive, affording you with more time to prepare. In this case, you may have as much as 30 minutes of warning time. If you live in the UK, you could have three minutes or less if the missiles are sub-launched, and about 15 if launched from land sites.

Should You Evacuate?

Evacuation is not recommended for several reasons. First, all routes out of your locale may be clogged with traffic. Or they may be blocked by police or military units so military or other official traffic can move freely. Plus, you run the risk of being killed or seriously injured by a nuclear explosion while trying to flee. Attempting to evacuate may also leave you with nowhere to take shelter when fallout starts arriving. And if you do survive, other survivors may not be willing or able to help refugees.

Evacuation makes sense only if the following conditions apply:

- You have days or weeks of warning that an attack is coming.

OR

- The attack has ended, fallout no longer poses any danger and the roads out of your town or city are passable.

AND

- The place you're going to has not been affected by the attack and unlimited amounts of food, water and other essentials are available for an indefinite period.

- You have sufficient amounts of food, fuel and water on hand for the trip to your refuge location and will not have to stop along the way to replenish any of these things.

- The route you're taking to your refuge location is not heavily travelled.

Effects of Nuclear Weapons

The graph below shows typical nuclear weapons effects, and the distances at which they occur.

‘HOB’, or Height of Burst, refers to the altitude at which the weapon was detonated. In this case, the weapon was detonated at a height of 1.4 miles above the ground. ‘GZ’ indicates Ground Zero, or the point where the weapon exploded. ‘PSI’ indicates the overpressure caused by the blast wave, in pounds per square inch. ‘1-MT’ signifies that the explosive yield of the weapon is one megaton, or the equivalent of one million tons of TNT.

The size of the nuclear weapon, or yield, will determine the distances at which various effects are seen. The greater the yield, the greater the damage. Conversely, smaller yields result in damage that is less severe and covers a smaller area.

When a nuclear weapon explodes, it generates five main effects. In order of occurrence, these are light, heat, immediate radiation, blast and radioactive fallout.

The light given off is intense. Some who have personally witnessed a nuclear explosion have characterized it as ‘ten times brighter than the noonday sun’. British servicemen who were on hand for various nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s were told to use their hands to shield their eyes from the light. Many recall that the light was so intense, they could see the bones in their hands. Looking directly at the light can cause permanent blindness or eye injury. You can avoid injury by shielding your eyes and turning your face away from the light.

At the same time as the light is given off, an intense, a brief pulse of heat is also emitted. To visualize how the immediate pulse of light and heat are linked together, try a little experiment. Hold your hand a few inches away from an incandescent light bulb. Now turn on the light. Note the sensation of warmth that you feel at the same time the light bulb illuminates.

The heat can cause first, second or third degree burns depending on how far away you are from ground zero. Up to half a mile away, the heat is so intense that people and most objects are simply vaporized. While standing outside and unprotected at a distance of 2.8 miles or less from ground zero, third degree burns to all exposed skin are likely. Heavy clothing can prevent such burns. Being inside a sturdy building made of brick or concrete, or even a typical wood-frame house may also offer protection, provided you are not standing in front of a window. Further out, at a distance of 7.3 miles, second-degree burns are possible. At 11.2 miles away, the vast majority of people who are outdoors will receive first degree burns.

Heat from a nuclear explosion causes serious fires to erupt over a wide area and generate a tremendous amount of smoke and poisonous gases. It can also cause a firestorm, in which the air becomes superheated and all available oxygen is sucked in from the surrounding area. People who are caught in a firestorm die rapidly from heat stroke and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Major fires or firestorms beyond 11 miles are unlikely, unless the yield of the weapon is greater than one megaton. However, some smaller fires may occur and spread.

Immediate radiation is another serious and lethal hazard. It is an intense, short-lived pulse of gamma radiation that occurs at the same time that the pulse of light and heat occur. Gamma radiation easily passes through all but the thickest materials. Accordingly, survivors within one mile of ground zero who are not sheltering in a very deep underground bunker will be exposed to the radiation. 100% of those who are exposed will be completely incapacitated and die in 12 - 24 hours. Treatment and recovery are not feasible.

Immediate radiation does not travel far and so does not pose any danger to people beyond one mile away from ground zero.

Aside from radioactive fallout, blast is the next greatest danger posed by nuclear weapons.

Within one mile of ground zero, the blast wave will cause total destruction of all buildings and other structures. People caught out in this zone die from being hit by flying glass and debris, from being thrown against walls or objects, being buried under rubble, or crushed. Severe injury is also very likely. The extreme pressure of the blast wave itself, can also cause death due to rupture of internal organs and collapsed lungs. This extreme pressure is called overpressure.

Further out, at distances between 1.1 to 2.8 miles, damage will progress from severe to moderate, with buildings severely damaged and uninhabitable. Injuries from flying glass and debris in this zone will be severe or fatal. Between 4.3 and 7.3 miles, damage will be moderate to light, and be progressively lighter the further out you go. Blast-related injuries will typically be moderate at 4.3 miles and minor at 7.3 miles. Some structures may be inhabitable in this zone. At the outer edge of this zone and beyond, damage will consist mainly of cracked glass and other minor damage. Virtually all structures in this area will be fully inhabitable. Injuries other than minor burns and cuts are unlikely.

Radioactive Fallout

Radioactive fallout is a major problem and will cause great loss of life and illness in a nuclear attack.

When a nuclear weapon explodes at or near ground level, it pulverizes and sucks up a tremendous amount of dirt and debris. This material is lofted high into the sky and becomes highly radioactive. It is then carried on the wind and begins to fall back to earth within 20 to 30 minutes after the explosion.

Radioactive fallout is so fine that it cannot be seen with the naked eye. The radiation emitted by fallout cannot be seen, heard, felt, or tasted, but it is extremely dangerous. Sometimes, fallout that lands close to ground zero may appear as fine dust that looks like grains of sand or tiny chunks of rock.

The air itself does not become radioactive because of fallout, but a strong wind can kick up and carry radioactive particles that can be breathed in or swallowed.

Radioactive fallout emits several kinds of radiation: gamma, alpha and beta. Gamma rays are very penetrating and can pass through all but the thickest materials. Exposure to excessive amounts of gamma radiation can sicken or kill. One inch of lead, 16 to 18 inches of concrete, or three feet of packed earth can stop 99% of gamma radiation. Other materials are less dense and therefore less effective. In order to achieve the same level of protection, greater quantities of these materials are required when building an improvised shelter.

Beta rays are far less penetrating and can be stopped by clothing and similarly light materials, but can also burn exposed skin.

Alpha rays are least dangerous and can be stopped by very light materials like paper, but they can cause serious illness if breathed in or swallowed.

What to do if You Receive Warning of an Attack

Follow all instructions given in the warnings. They may save your life. Do not use the telephone, or your mobile phone, as the lines will be needed for official use. Do not panic, or cause panic, or spread rumours about the attack.

If you are outdoors after receiving a warning, head to the nearest large building and take shelter there. If there are no buildings nearby, take shelter in a culvert or ditch, or get underneath your car. If you have a shovel, dig a trench and shelter underneath your car. The trench should be at least three feet deep. When digging the trench, shovel the dirt onto the lower sides of the car to provide additional shielding against fallout.

Try to remain sheltered there for at least 72 hours if you can, before moving to find better shelter or food and water. In 72 hours, a significant proportion of the radiation emitted by the fallout will have decayed to safer levels. However, don’t spend any more time unprotected than is necessary, as dangerous hot spots may remain.

If you see an extremely bright flash in the sky while outdoors, drop to the ground immediately, lie face down, and cover your face, head and hands with clothing to prevent flash burns. Take the same actions if you are sheltering in an open trench. Do not look at the flash, or you may be permanently blinded. Wait two minutes for the blast wave to pass before getting up to find better shelter.

If indoors, immediately go to the lowest level of the building. Take food, water, a flashlight and battery-powered radio with you, along with extra batteries. If time permits, turn off all water, gas and electricity supplies to reduce the risk of fires or explosions being triggered by the blast wave. Close all windows and doors. Leaving your doors unlocked will help rescue workers come to your aid if your home has been badly damaged by blast. Whitewash and tape up windows to prevent fires from breaking out inside your home and prevent glass from being blown in by the blast wave. Remove all flammable materials like paper from your home and dispose of them in closed garbage receptacles stationed outside.

If there is not enough time to assemble necessary supplies or complete essential tasks, take cover and wait for the blast wave to pass before going back to get them or completing the tasks.

After the blast wave passes, you will have 20 - 30 minutes to get extra food and water or other essential supplies before dangerous radioactive fallout starts coming down. If you do not need extra supplies, use the time to build an improvised shelter, put out fires and make minor, essential repairs. If sheltering in a house or apartment, fill up all tubs with water before turning off the water supply. Cover the tubs with a wooden board or cling wrap. This will protect the water from being contaminated by any radioactive fallout that might enter your home through air vents or broken windows.

If you are with a group of people, delegate various essential tasks. For instance, you can delegate one or two people to find extra food and water. Several people can work on building an improvised fallout shelter, while another group of people can be tasked with getting blankets, bedding, warm clothing, books and games, and so on.

If it is not safe to remain where you are, then use the time to find better shelter. Don’t spend more time outside than absolutely necessary. However, spending a few extra minutes is fine if the tasks you need to carry out are essential to your survival, although you may run a risk of being affected by radiation sickness later.

Where there is no basement, shelter in a central room where there is only one door and no windows, to protect yourself from flash burns, flying glass and debris. While going to the central room, avoid passing by or standing near any windows..

In a high-rise building, select a central room on a middle floor to get protection from radioactive fallout. Do not shelter in any of the three uppermost floors, as they will not provide enough shielding from fallout.

When sheltering in a central room in any building that does not have a basement, you will need to build an improvised fallout shelter to increase your protection from radiation. However, if you are sheltering in a house that has a basement, an improvised shelter is still required. If there is no central room, choose a room with no windows, and build the shelter as far away from exterior walls as possible.

An improvised shelter may not be required if your shelter location is the basement or sub-basement of a high-rise building, where the shielding will be optimal, or near-optimal.

You can construct such a shelter out of heavy furniture, boxes of books or papers, boxes or bags of dirt or sand and any other heavy, thick materials.

The image below gives more details on how to build an improvised shelter. Make sure that your shelter is well protected on all sides, but leave an opening where you can enter and exit. The thicker the walls and roof of your shelter are, the better the shielding against radiation.

Books, boxes of papers or other heavy materials will not provide as much protection as concrete or packed earth do, so more of them will be needed to approach the same degree of benefit. The protection factor, or PF, offered by the building itself can reduce or eliminate how much shielding you will need when building an improvised fallout shelter.

Shown in the graphic are the protection factors (PF) offered by various kinds of buildings. For instance, the basement of a large high-rise building can yield a PF of 200, which means that the radiation level inside that part of the building will be 1/200th, or 0.005% of what it is outside.

Hence, if the dose rate outside is 3000 rads per hour (R), the protection offered by the basement will reduce the dose to 15R per hour.

A dose rate that high would not typically be seen unless you are situated one or two miles away from ground zero. Radiation from fallout grows progressively less intense the further away from ground zero it travels. As a general rule, it decays or diminishes by a factor of 10 for every seven hours that pass.

All exposure to radiation is cumulative. Therefore, regardless of where you are sheltering, you will need to remain there for 14 days to minimize the accumulation, unless officials instruct otherwise.

For example, if the dose rate outside the basement is 500 rads per hour, the protection offered by the basement will reduce it to just 2.5 rads per hour, which is a very low dose. Usually, a dose of 500 rads will kill anyone who is standing outside and unprotected for one hour. Seven hours later, if that person is still standing outside, they will have received a staggering total of 3,500 rads. In the basement offering a PF of 200, the total dose in seven hours will be just 17.5 rads. This is not enough to cause death, any degree of radiation sickness, or even elevate the risk of getting cancer in later life.

Seven hours after that, anyone sheltering in the basement would receive an additional dose of just 1.75 rads. Three days later, the radiation in the basement will have decayed to near-normal levels of background radiation.

Naturally, improvised shelters in buildings with lower protection factors will not provide as much protection. Therefore, the dose of radiation that people will receive while taking cover in such shelters will be substantially higher.

If your area was not hit with a nuclear weapon, do not assume that you will not be affected by fallout. Fallout can travel for hundreds of miles before coming down. Changing wind speeds and directions can cause the fallout can go anywhere and everywhere, and land in unexpected places.

The good news is that if fallout is not expected for several hours, you will have plenty of time to prepare for its arrival. If the fallout is light, you may not need to do much more than simply stay inside your house or apartment for a few days.

Monitor your radio for instructions to learn when the fallout is expected, and what you need to do to protect yourself. You will also be told when it is safe to leave your shelter. You may also be advised that you can leave your shelter for brief periods and then return later. As radiation continues to decay, you may be able to spend progressively longer periods of time outside without exposing yourself to danger. But don’t take any chances; radioactive fallout can be deadly.

Be aware that in a general nuclear war, many places will be targeted with nuclear weapons that are detonated high in the sky instead of ground level. These are called airbursts. Airbursts cause destruction over a much wider area, and tend to generate little or no fallout. You will not be able to determine ahead of time whether your area will be subjected to an airburst. Therefore, assume that fallout will affect your area, and take steps to protect yourself.

Download our handy guide, Nuclear Attack - Immediate Actions on Warning here:

Nuclear Attack - Immediate Actions on Warning

You can use the guide as a quick reference if an attack happens. Make a copy of it and store it on your mobile phone, or tablet computer for quick access in an emergency. Or print it and carry it with you.

Radiation Sickness

Overexposure to gamma radiation causes sickness or death by damaging internal organs, red and white blood cells. This is called radiation sickness. Radiation sickness is a major cause of death and serious injury in a nuclear attack. It can be mild, moderate, or severe. Below is a chart showing the various degrees of radiation sickness and how they can be managed.

During the Attack and in the Aftermath

If you must leave your shelter to complete essential tasks while fallout is coming down, put on a broad brimmed hat, a coat and rubber boots or other footwear you can remove easily and quickly. Wear goggles and a disposable facemask to prevent particles of fallout from getting in your eyes, or to avoid breathing them in or swallowing them.

Just before you go back inside, brush any radioactive dust off your hat, clothing and boots. It’s a good idea to wash your boots if possible. Simple dish soap, water, a bucket, and a household brush are sufficient for the task. After washing your boots, dispose of any waste water outside, or throw it down the drain of a bathroom you are not going to be using.

Next, take off all your clothing including any undergarments and boots, and place the clothing in garbage bags or bins. Make sure the bags or bins and boots are placed well away from your improvised shelter. Throw the face mask in a garbage pail that is located well outside your shelter room.

If you can, take a shower. Otherwise, wash your face, hands and hair. Clean under your fingernails.

Put on fresh, clean clothing before reentering your shelter. By completing these tasks, you can avoid contaminating your shelter with fallout.

To conserve battery power, monitor your radio at the beginning of each hour for official news, updates, and instructions. If you have plenty of batteries, it may be psychologically helpful to listen to music broadcasts on your radio, if they are available.

If sheltering at home, remember that even if the power is out, your refrigerator can keep food cold for up to 24 hours. Frozen food in freezers will remain frozen for up to two days. Therefore, consume refrigerated or frozen foods first, if you can.

Food does not become radioactive. Some fallout dust can accumulate on fruits, cans or packaged foods. Simply remove the dust from cans or packages with a clean cloth before opening them. Fruits can be washed in cold water before consumption.

For toilet facilities, set up a plastic bucket that has been lined with a leak-proof plastic bag. Construction-grade bags are a good choice for this purpose. Place a small amount of disinfectant and deodorizer in the bottom of the bag, to control odours and reduce the risk of spreading infections to others sheltering with you. Make sure that full waste bags are stored well away from your shelter, or stored outside in closed garbage bins.

If someone in your shelter group dies, attach a tag with their name, date of birth and next of kin to their clothing. Write down the cause of death, if known. Then wrap the body in heavy plastic. Non-transparent vapour barrier sheeting and duct tape work well for this purpose. Otherwise, use large construction-grade plastic bags. Bury the body in a shallow grave outside your home. Mark the grave with the deceased’s name so it can be identified later. If it is not safe to go outside, store the body in a place that is well away from your shelter, and bury it as soon as possible.

Do not expect immediate rescue, assistance or resupply from emergency response officials. The attack may destroy or severely impair existing police, fire and ambulance services and their ability to function.

Even if these services remain functional to some degree, it may take days to several weeks for them to regroup, rebuild and provide help. If national or sub-national governments have survived the attack, their efforts to mount a relief operation will take time. Coverage of relief efforts may be patchy.

Water, electric power and other utilities may or may not be restored after an attack. Mobile phone and internet services may also not be restored. Mobile phone networks, if restored, may be local, ad-hoc networks only with only limited service available.

Long-range Preparations for an Attack

One of the biggest difficulties in preparing for something like a nuclear attack is the impossibility of predicting when, or if, an attack is going to happen. A nuclear war is most likely to happen after a period of international tensions leads to a world war, and the warring countries resort to using nuclear weapons to either win the war, break a stalemate, or avoid losing.

Chances are good that you will likely receive plenty of advance notice that the probability of a nuclear attack is high, and you will have time to prepare. Needless to say, it would be a good idea to start preparing as soon as war breaks out, or earlier, if possible. Grocery stores are likely to be quickly overrun and stripped bare the minute the news media start issuing big hints that a nuclear war could be on the way, and the government confirms the reports.

You could try to prepare by buying a lot of freeze-dried or tinned foods with very long shelf lives. Sooner or later, though, you will have to consume these foodstuffs before they expire.

A more practical solution is to always have extra supplies of tinned and non-perishable foods on hand, enough to last 14 days, and rotate them as they approach their expiry dates. The downside is that you will always have to spend a bit more on groceries to keep your supplies reasonably fresh.

If you’re an apartment dweller, or you live in a house where there is no basement, you can designate a central room as a shelter and pre-position things like cots, blankets or sleeping bags, a battery-powered radio, lanterns and other supplies so they are readily accessible in an emergency.

It’s also a good idea to stock your shelter with books, games and notepads to pass the time while riding out the worst of the attack. Add blankets, bedding and warm clothing, too.

If you work full-time in an office or industrial site, it’s not a bad idea to store a small quantity of food and water there. Perhaps you won’t have the space to store a full 14-day supply, but you might have enough room in your desk or locker to cover a 72-hour period.

Download our handy list of supplies that should be in your shelter room here:

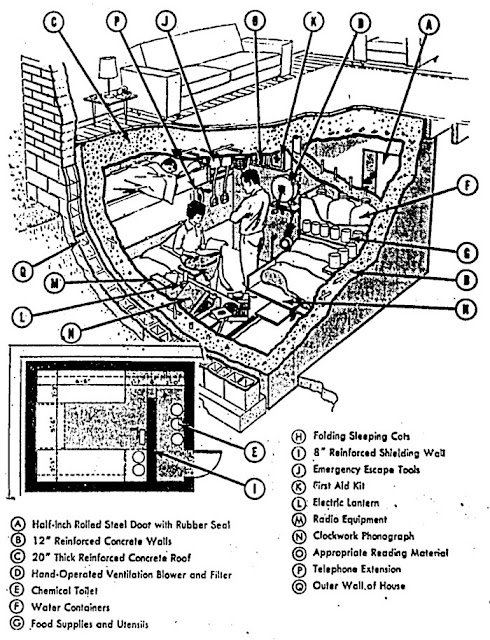

If your home has a basement, you’ll have even more space to store essential supplies and room to build a more permanent shelter, like the one shown below.

There are arguments for and against building one. For starters, if you’re at home when warning of an attack comes, your shelter will be close by and it will already be stocked with supplies. You won’t experience the stress and pressure involved in trying to build an improvised shelter during an attack and fallout is on the way.

A dedicated shelter, if properly constructed, can also give you better protection against blast, heat, and fallout. If your home is severely damaged in an attack, you will have access to at least a semi-permanent form of housing in the aftermath.

Cost is the biggest disadvantage to building a purpose-built shelter. In addition, in order to provide a safe refuge, a dedicated bomb shelter has to be engineered and built correctly, thus requiring you to hire specialists to handle the design and construction.

Then there are legal hurdles. Some jurisdictions do not allow the construction of private bomb shelters. In jurisdictions that do, you may have to spend a lot of money to obtain the necessary permits and clearances. Moreover, securing the permits may take considerable time.

If your neighbours know about your shelter, they may come knocking on your shelter door, or worse, may try to break in while the warheads are on their way.

Finally, if you are at work and a nuclear war breaks out, you may not be able to reach your shelter at all, or reach it in time. The same problem will crop up if you are away from home or travelling.

If you work from home, don’t leave home often and don’t travel, then a dedicated bomb shelter might be a good idea.

Conclusion

A nuclear attack is survivable, provided you don’t live in a major city or near a military base, take timely action when warning of an attack is issued and take cover. Survival prospects can also be improved by preparing in advance for an attack.

References

There are several excellent, out of print references available on how to prepare for, and cope with a nuclear attack. Most of the advice they provide is still relevant today.

One of the best references is 11 Steps to Survival, which was published by the Canadian Department of National Defence in conjunction with the Emergency Measures Organization in 1969 and reprinted in 1980 and 1986. You can find a copy here: 11 Steps to Survival.

Another good guide, from the UK Home Office, is Protect and Survive (1980). A copy can be obtained here: Protect and Survive. For an up-to-date, although less detailed online reference, go here: Nuclear Explosion.

Comments

Post a Comment